December 2005 in New York City was cold and wet. Members of Trinity Lutheran Church in the Upper West Side of Manhattan were grateful for the warmth of the church’s walls as winter began to set in. But their hearts were heavy, knowing that a growing number of unhoused young people were out on the streets in miserable weather.

The Rev. Heidi Neumark, then pastor of the congregation, had preached a sermon inspired by a New York Times article describing the rapid rise in the number of LGBTQ+ youth living outside in recent years. Many had left unaccepting hometowns and migrated to New York seeking belonging and the freedom to live authentically. But many ended up without sufficient income or shelter, and only 12 beds for LGBTQ+ youth existed in the city. Trinity was saddened to learn that these young peoples’ dreams were dashed by harsh reality.

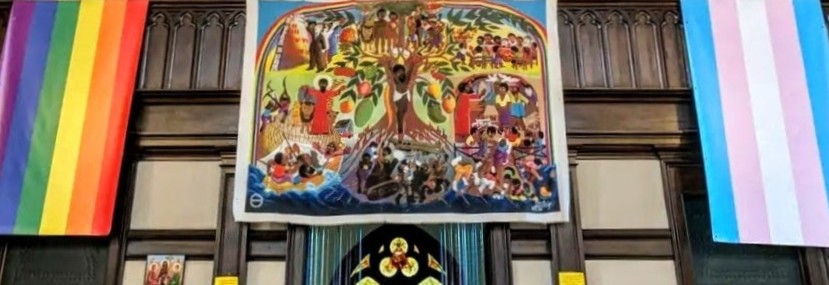

The church had a long history of advocating with LGBTQ+ neighbors and organizations. During the height of the AIDS crisis, members took the bold step of hosting programs for their neighbors living with HIV, which evolved into a scattered-site housing system in East Harlem. The recent news stories about LGBTQ+ homeless youth called to members’ deepest sense of mission — they knew they had to do something.

By 2005, Trinity’s membership had declined significantly, and the church was operating at a financial deficit. Members felt called to act but felt they had no resources to offer. What the church did have was space — and a good amount of courage.

When New York State Pride reached out to churches asking for shelter space during the coldest months of the year, Trinity answered the call. Vicar Chris Wogaman led the effort — the state would provide bedding and cots, and Trinity would provide overnight supervision, dinner and breakfast. The three-week pilot program was so successful that two Pride members offered to keep the shelter going full time. Trinity got seed funding for a year, and the congregation began exploring ways to enhance the program.

“This was a huge leap of faith for them,” said the Rev. Alyssa Kaplan, current pastor of Trinity. The congregation was often operating at a deficit and had faced serious challenges before calling Pastor Neumark. Trinity took this leap not when it was stable or had an excess of funds but at a time of scarcity.

“They knew that churches had hurt the LGBTQ+ community, that churches were one of the reasons why these youth were on the streets. They saw that it was incumbent on their church to be part of the healing process.”

- Rev. Alyssa Kaplan

The congregation was willing to put everything on the table to keep the program running, and in June 2006, they unanimously voted to establish Trinity Place Shelter as the permanent shelter program, and it’s been open every night since.

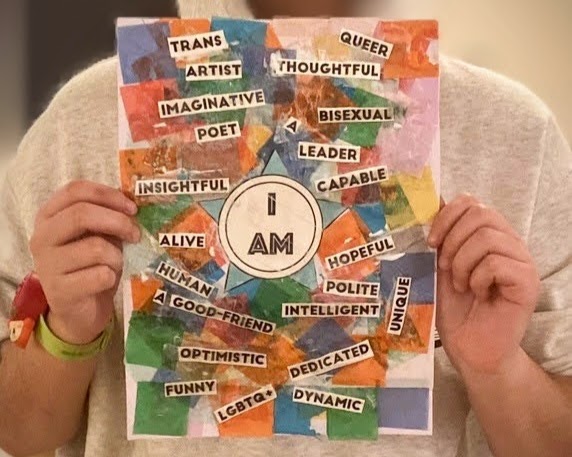

The church is not large — a modest sanctuary sits atop a basement fellowship hall, two staff offices, a kitchen and two small restrooms. Shelter guests arrive in the late afternoon and help transform the fellowship hall, which is often in use during the day for other programming, into a shared sleeping area with cots and a central dining table. The guests are young adults ages 18 to 24 and may stay at Trinity Place for up to 18 months.

Having a reliable and safe place to sleep, cook, unwind and store belongings is critical. It helps residents maintain employment, pursue education, engage in needed services and take necessary steps toward more permanent housing. The shelter accommodates about 10 guests — the maximum the space allows — creating a sense of community.

Like the building, Trinity Place’s organizational infrastructure has stayed small but mighty. In 2006, its board was made up of all congregation members, and staff were volunteers. Grant funding was available but only for proven programs. Trinity used the seed funding to build a program structure, and Wogaman declined a salary for two years while serving as director. Slowly, but surely, Trinity Place secured grant funding, hired (paid!) staff, and transitioned from a crisis shelter to a longer-term model.

Today the church still supports the program through funding (including ELCA World Hunger grants) and volunteering. The pastor remains the executive director of the shelter, but it is now a self-sustaining and independent partner. Trinity Place provides a monthly contribution for the use of space and splits many occupancy costs with the congregation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the shelter accessed capital funding to renovate the fellowship hall, making it more welcoming and functional. In 2026, the church and shelter plan to embark on a collaborative capital campaign, leveraging public and private funding to restore and upgrade the facilities. The big goal is to achieve total accessibility for the property.

Trinity Place was born from a congregation that proclaims “a wild belief that with God and one another we can make a difference.” For hundreds of LGBTQ+ youth, they have. The church building has become more than a house of worship, it is a place of shelter, healing, safety and love. The bold step that Trinity took 20 years ago has sustained not only the congregation’s mission in Manhattan but their physical presence — which may, in fact, be one and the same.

Property Stewardship Lessons

- Your assets serve your mission, not your budget. Don’t be afraid to dip into endowments, bequests or savings accounts if that money will help you answer God’s call.

- Create a mission partner if you don’t already have one. Separate 501(c)3 organizations build capacity beyond church volunteers and funding.

- You don’t need a big church to do big things. God asks us to do what we can, with what we have, where we are.