When Bethlehem Lutheran Church closed in 2010, the remaining members of the congregation had a dream: to leave a legacy of affordable housing in their rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of Seattle. They signed an agreement with Compass Housing Alliance, which committed to building housing and preserving church space on the property within 10 years, and engaged the Northwest Washington Synod to hold that agreement in trust.

“That dream allowed them to walk away,” said the Rev. Darla DeFrance, who serves Columbia City Church of Hope, the new worshiping community that was planted on Bethlehem’s property. “The problem is, they walked away from the development process too,” added Jay Edgerton, director of properties for the synod. Pastor DeFrance and Edgerton have worked for many years to make that dream a reality, which they admit is only happening by the grace of God.

Bethlehem’s building continued to sit unchanged for several years after the congregation closed. Compass Housing Alliance struggled to finance the project, and all the while the building was racking up costs — maintenance, utilities and insurance. As Bethlehem worked through the property transfer, the synod approached Pastor DeFrance with the offer to start a new congregation in the old building. The synod hoped that having an active congregation with a strong pastor would help move the development project forward. The new congregation tried to shepherd the vision as best they could and worked with Compass to explore different opportunities. Since they didn’t own the building, however, Church of Hope didn’t have a legal stake in the project and there was only so much advocacy they could do.

While the synod was the partner with legal pull, it was not equipped to shepherd the project. “Synods aren’t landlords,” Edgerton said. “They had this complicated asset, and no one could pay attention to it.”

Since no one at the synod office “owned” the project, no one was assigned to advocate on its behalf. Edgerton joined the synod staff as a part-time real estate consultant in 2020 and was given the Columbia City Church of Hope project as his first client. After just a few conversations with Pastor DeFrance, Edgerton was determined to see the vision through. The church and synod now had an advocate with the experience and expertise to engage with development partners on equal terms.

“A church needs to be here. This community deserves to have a house of worship always looking out for their interests, always looking for ways to serve their neighbors.”

- Jay Edgerton

2020 also happened to be the deadline for a housing development project to start. If it didn’t move forward, the property’s future was even more uncertain. It was clear by that point that Compass Alliance did not have a viable plan for development. Pastor DeFrance had built a relationship with the group’s affordable housing consultant, Beacon Development Group. But Beacon was hesitant to work with the church directly since previous projects with congregations had floundered.

“Churches move at a glacial pace,” said Brian Lloyd, a vice president at Beacon. “And if there’s a change of leadership, or if there’s a new focus in the congregation, all that work gets left on the table.” But in Columbia City Church of Hope, Lloyd saw that the newer, smaller congregation, with an energetic pastor, was totally bought in. Beacon talked to another client of theirs, El Centro de La Raza, who was better positioned to lead the project. El Centro de La Raza purchased the land from Compass Housing Alliance, and they got to work designing their own development.

El Centro, Columbia City Church of Hope, and Beacon were now all working together to get the affordable housing development off the ground. They learned quickly that the partnership would only work if they all leaned into their individual strengths and trusted the others to lean into theirs. This was especially true for affordable housing in Washington state. “It is ridiculously complex and one of the stupidest processes I’ve ever seen,” Lloyd said. “Shoveling projects through that maze is really hard.” The church let El Centro and Beacon navigate the design process and piece together the financing — a mishmash of tax credit sales, grants and loans.

“In almost all aspects of the congregation, our church is highly collaborative, but this building project is not,” Pastor DeFrance said. The small building team helped El Centro and Beacon with community outreach and investment, but then they stepped away.

“Congregations can’t vote on every aspect of the deal. This is complicated stuff and it’s too easy to get bogged down in details we don’t understand.”

- Rev. Darla DeFrance

What the church could do, better than El Centro or Beacon, was cultivate relationships with the surrounding neighborhood and the Bethlehem community, the original donors of the property.

The church planned community celebrations of project milestones and made sure that those donors and the church’s neighbors were on board every step of the way. That engagement demonstrated to Beacon and El Centro that the church was not a second-tier collaborator but a full partner in the project. It was Edgerton’s idea to structure the ownership of the development in a way that honored the collaborative roles that each entity would play in the community.

Instead of a simple ground-lease of church property to El Centro or for that organization to lease back to the church, they entered into a condominium agreement. This allowed each member’s autonomy but also held them accountable to respect and cooperate with the others. The condo arrangement would allow Columbia City Church of Hope to continue to have full agency in ministry programs, mission and outreach without being beholden to one of the other entities for permission.

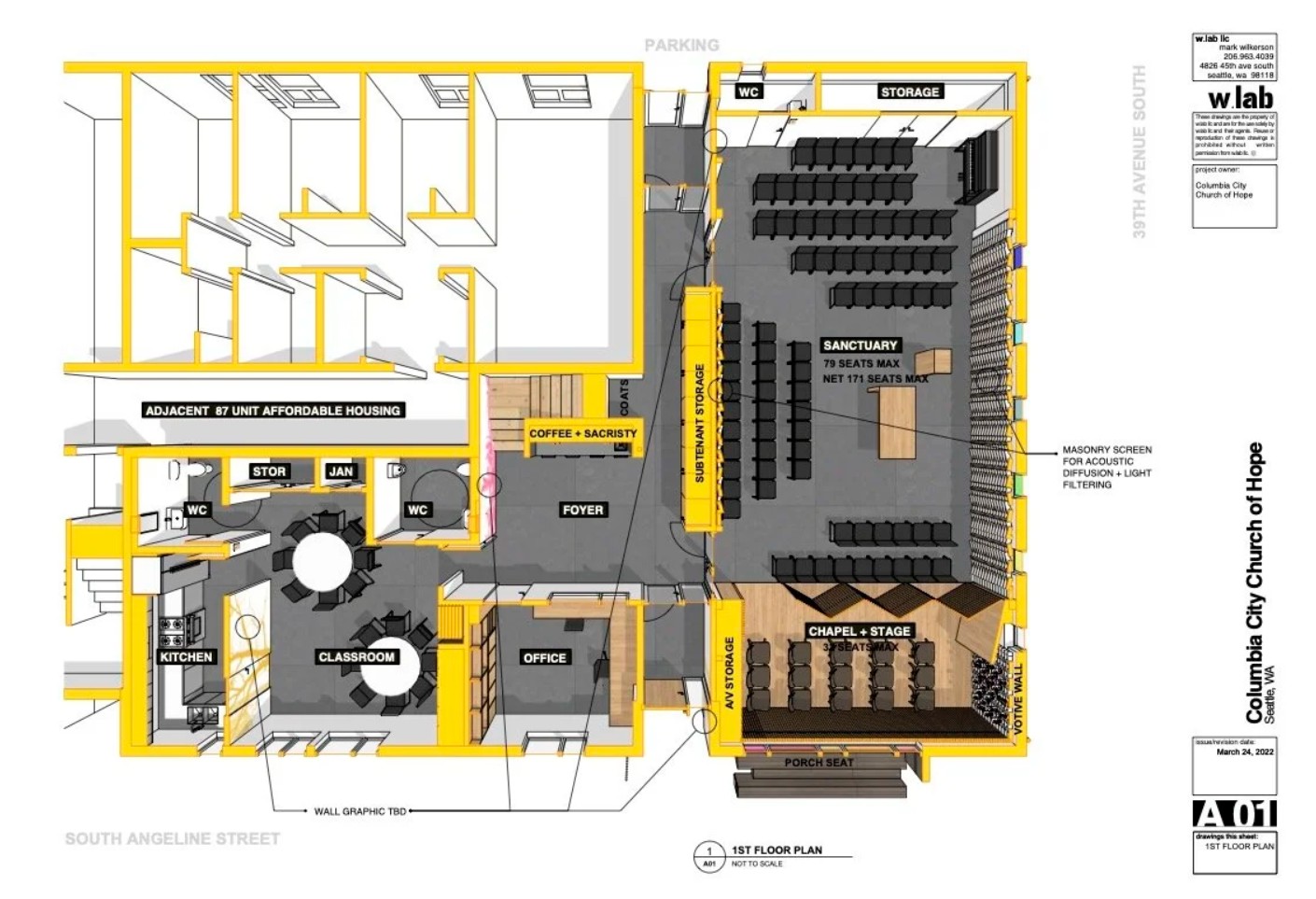

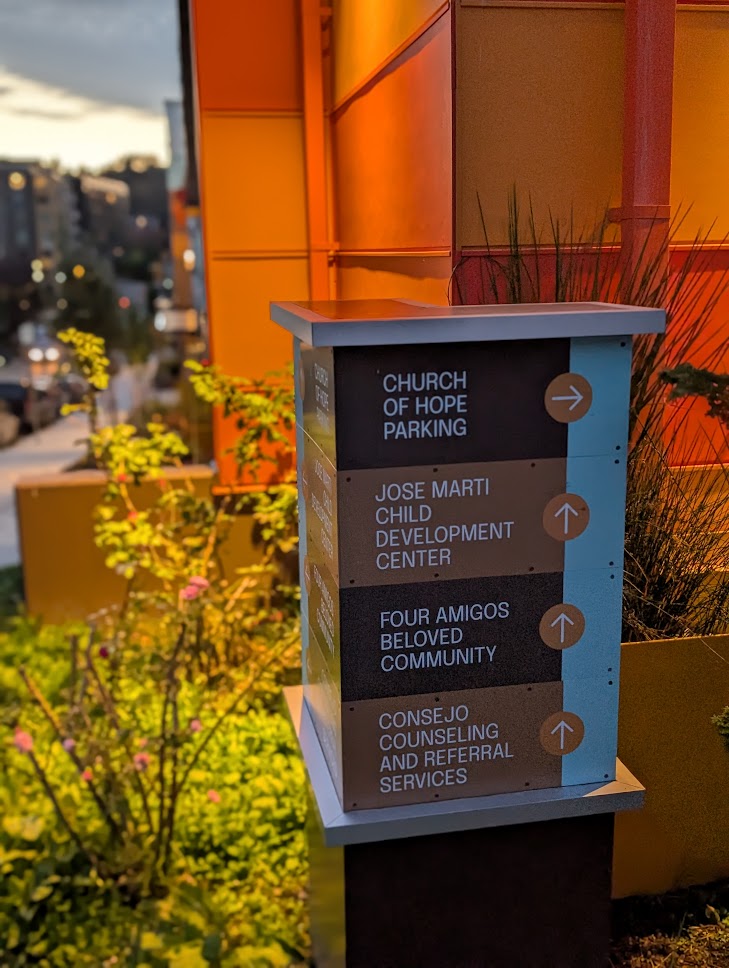

Fifteen years after Bethlehem first donated the property to Compass Housing Alliance, the development project is reaching the finish line. The Four Amigos Housing development includes a 2,600-square-foot church space for congregational activities and community-serving programs; a 6,600-square-foot dual language, multicultural child development center with four classrooms and outdoor play space; and 87 apartments in a single, six-story building.

The project has attracted attention from the city of Seattle’s Office of Housing, and they will help to anchor a new transit project that will invest in the commercial corridor that the Four Amigos sits on. While Pastor DeFrance, Lloyd and Edgerton are immensely proud of this project, they shake their heads recounting the long, winding road they took to get to there. When asked what advice they would give to other congregations thinking about affordable housing developments, they quickly named a long list of mistakes they wish had been avoided.

Property Stewardship Lessons:

- Work with the synod early to articulate your vision. “Don’t encumber a real estate asset with a plan and then ‘gift’ it to the synod,” Edgerton said. “You give an impossible gift. If a church wants to leave a legacy in their building, they need to work with the synod to articulate the dream and then the synod can ensure they have the expertise to see it through.”

- Let the experts be experts. “Don’t deceive yourself in thinking you know more than a real estate professional,” Lloyd said. “Discern a desire and then commit to a development partner who knows how the real estate world works.”

- Stay flexible as a project develops. “Don’t marry yourself to a particular vision,” DeFrance said. “When you turn over a property, you have to understand that it has a future of its own.”